Urner Boden

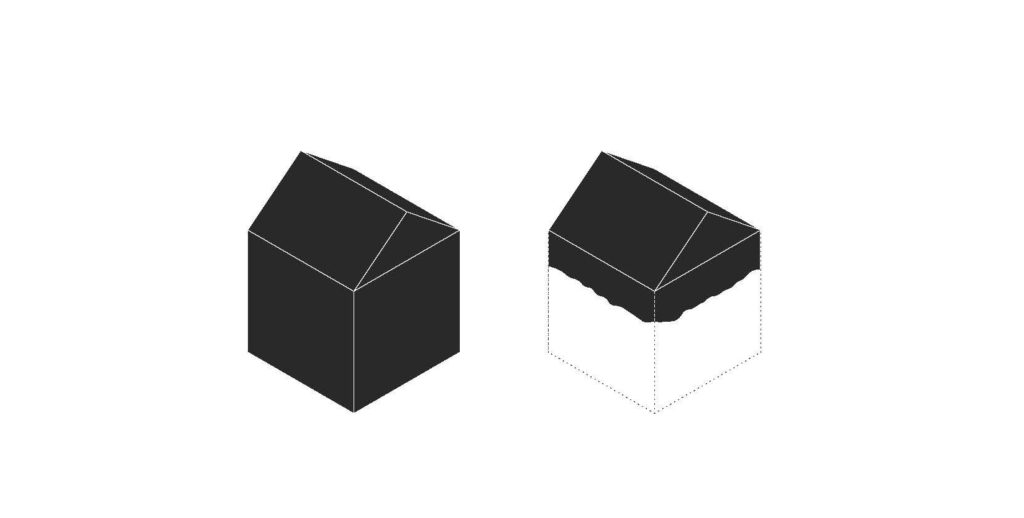

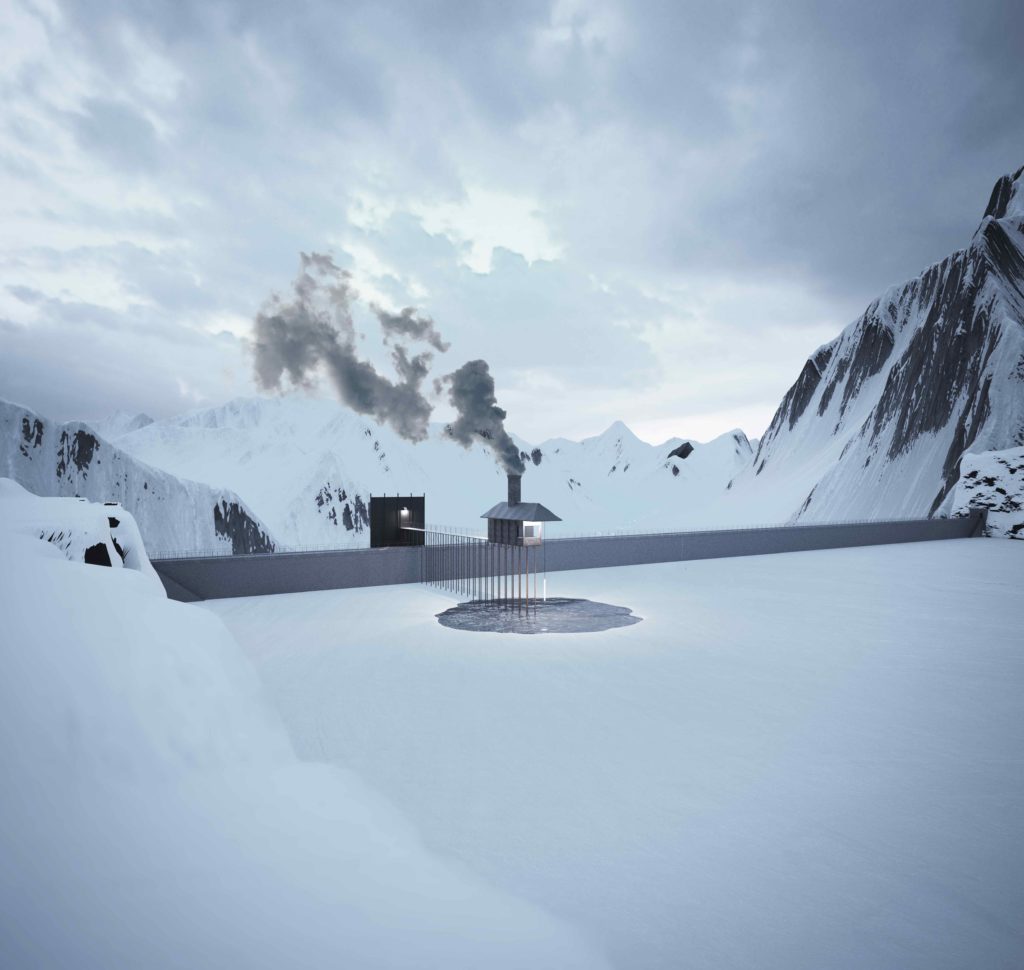

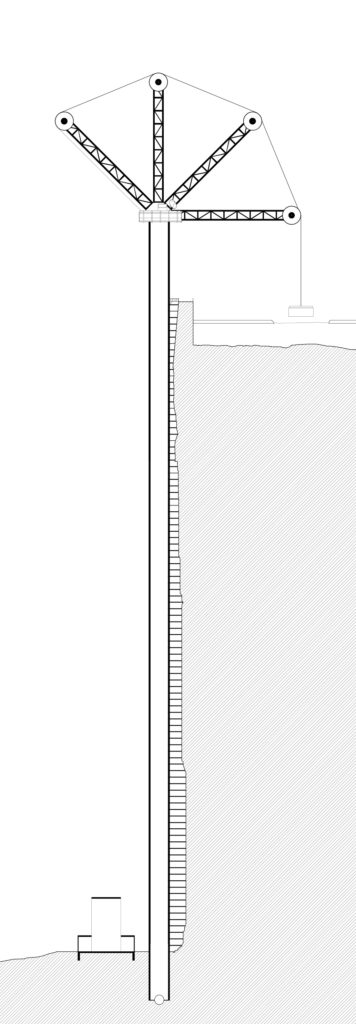

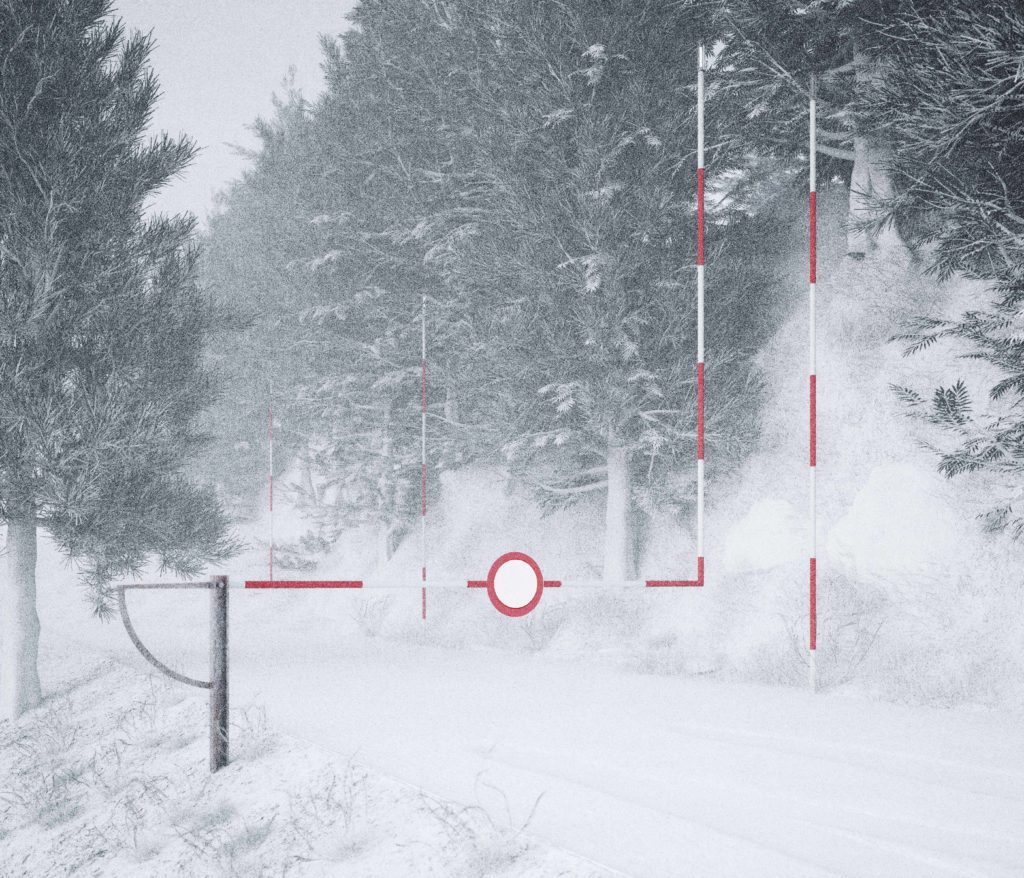

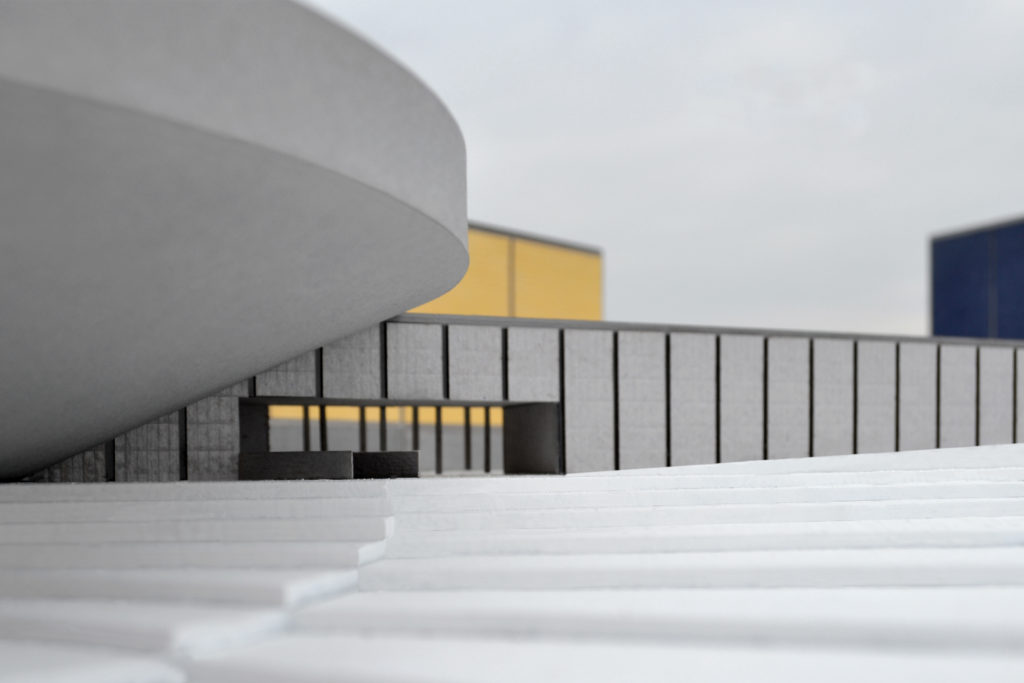

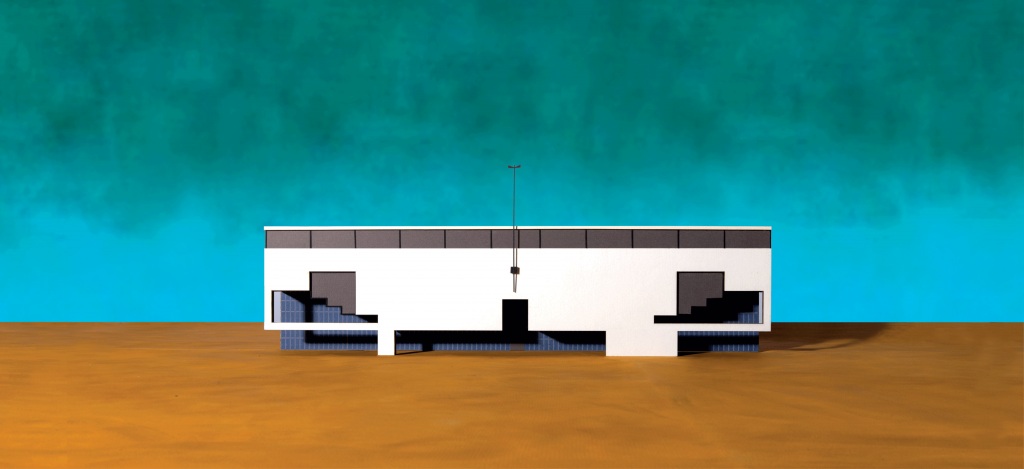

When there are five meters of snow on the landscape, there are two levels: the level of the ground and the top of the snow. The project 27 Smoking Chimneys examines the effects of this fact on the architecture and social identity formation in the Swiss Alps.

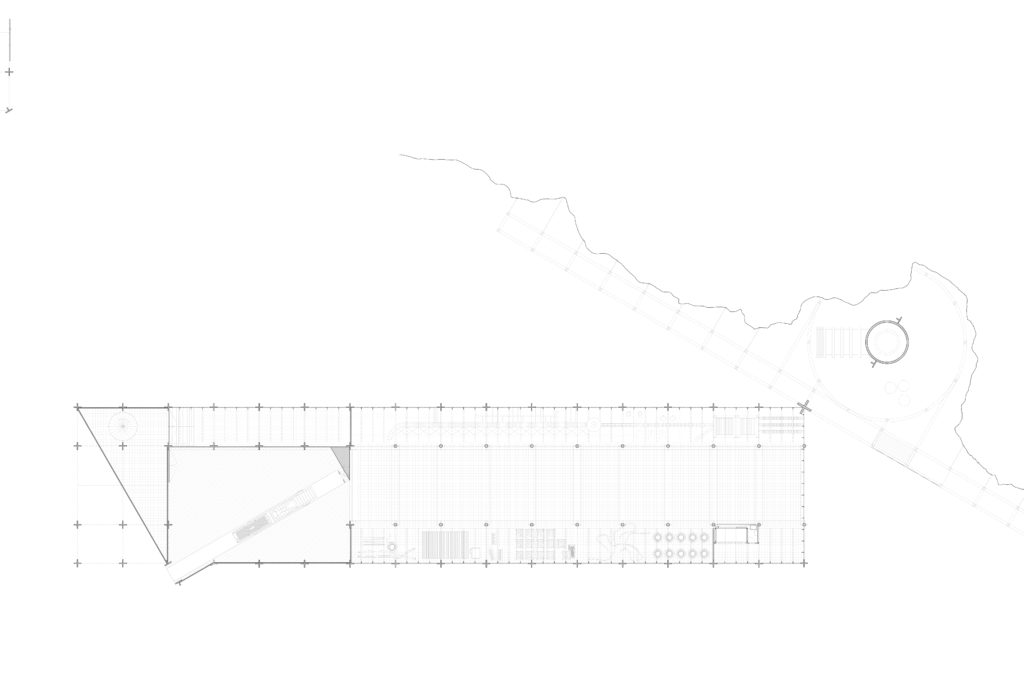

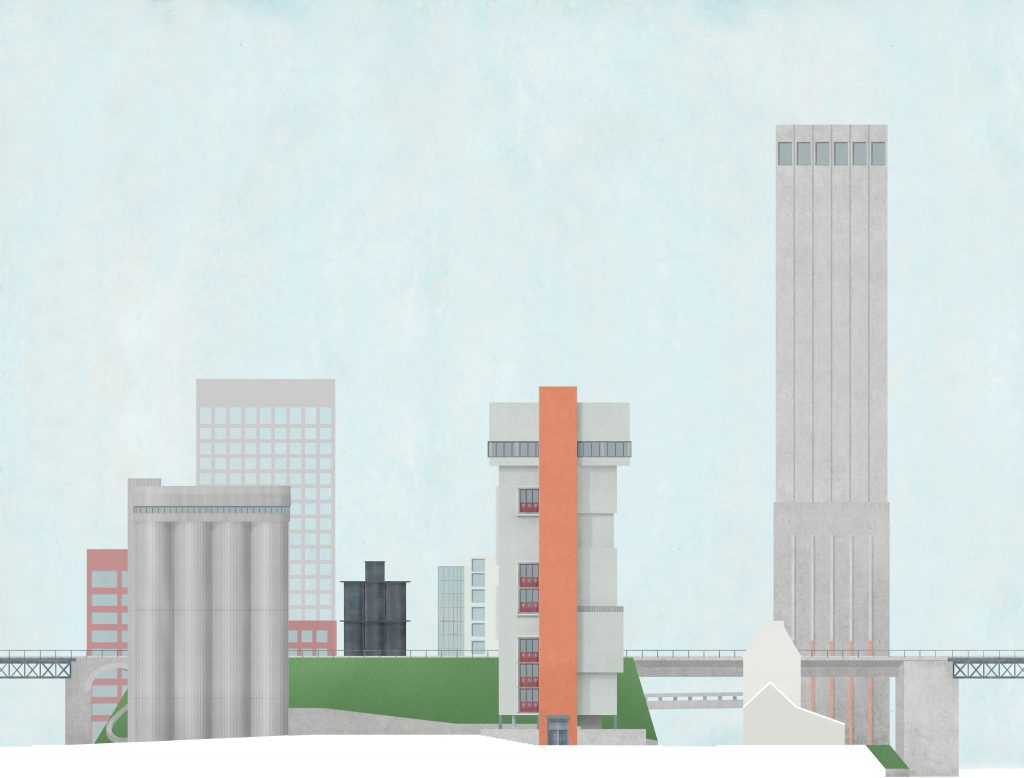

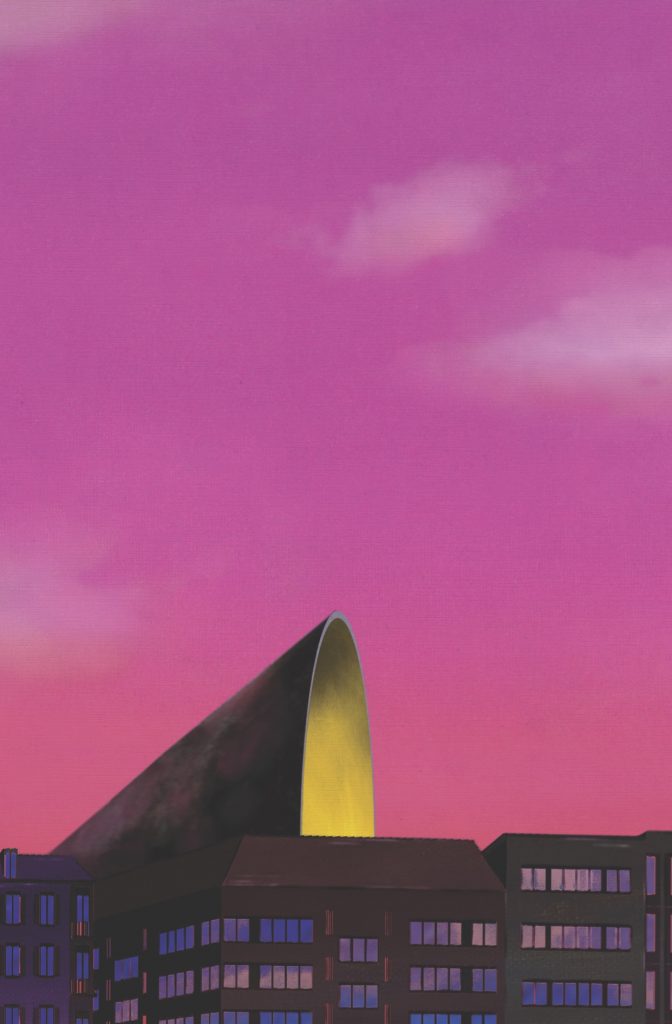

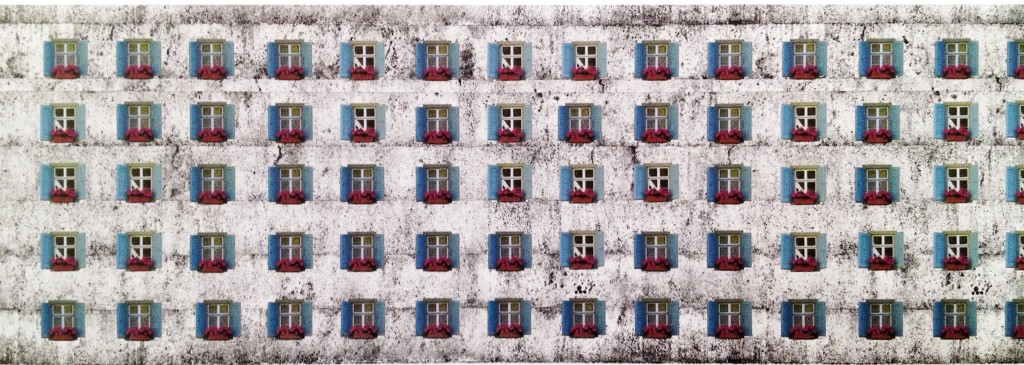

A Grisons architect described some time ago a mountain village as an agglomeration. Precise but provocative this seemed in our ears, incompatible with the wishful thinking of our mountains. Certainly, the effectiveness of the statement was at least partially in the veracity of this statement. This made mountain villages appear as places of contextual openness, where the importance of the built environment is no longer self-evident and the frame of reference is stretched ever further. The individual village was only a case study of a major crisis. The project ’27 Smoking Chimneys’ focuses on the latent identity of the Urnerboden, a plateau in the canton of Uri. As in many places, the historical fabric is emulated by plastic shingles and vinyl parquet floors, A visual coherence is only visible in the remnants of the past. We do not regret this tendency from sentimentality or nostalgia, but because such a retrospective mixes together a gray architectural value. It produces an indistinctness without its own identity, a spongy imitation of the built cultural heritage without adding value. The image of this “crisis of the gray value” are actually the last 27 winter inhabitants of the Urnerboden. We postulate that this gray value can be covered by a pure white – the snow. The snow is the most multilayered of all opponents, an opposing position to the architectural gray value; a pure white which covers the landscape. He associates images and provokes architectures, which belong to a collection of accurate caricatures and structures that permanently manifest the temporary, cyclical state of snow. From its elevated position, the Urnerboden looks in the longitudinal direction in the Glarus region. At the far end of the valley, the Klausenpass snakes up a steep slope and disappears over a height. As a figure, the plateau is composed of clear elements. It has a beginning and an end, two opposite sides and a large area in between. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains. cyclically recurring state of the snow permanently manifest. From its elevated position, the Urnerboden looks in the longitudinal direction in the Glarus region. At the far end of the valley, the Klausenpass snakes up a steep slope and disappears over a height. As a figure, the plateau is composed of clear elements. It has a beginning and an end, two opposite sides and a large area in between. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains. cyclically recurring state of the snow permanently manifest. From its elevated position, the Urnerboden looks in the longitudinal direction in the Glarus region. At the far end of the valley, the Klausenpass snakes up a steep slope and disappears over a height. As a figure, the plateau is composed of clear elements. It has a beginning and an end, two opposite sides and a large area in between. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains. At the far end of the valley, the Klausenpass snakes up a steep slope and disappears over a height. As a figure, the plateau is composed of clear elements. It has a beginning and an end, two opposite sides and a large area in between. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains. At the far end of the valley, the Klausenpass snakes up a steep slope and disappears over a height. As a figure, the plateau is composed of clear elements. It has a beginning and an end, two opposite sides and a large area in between. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains. In summer, the twelve-kilometer-long ground acts as a stopover, a horizontal plane which is clamped between two undulating pass roads. In winter, the Urnerboden is a dead end, a white prairie surrounded by high mountains.

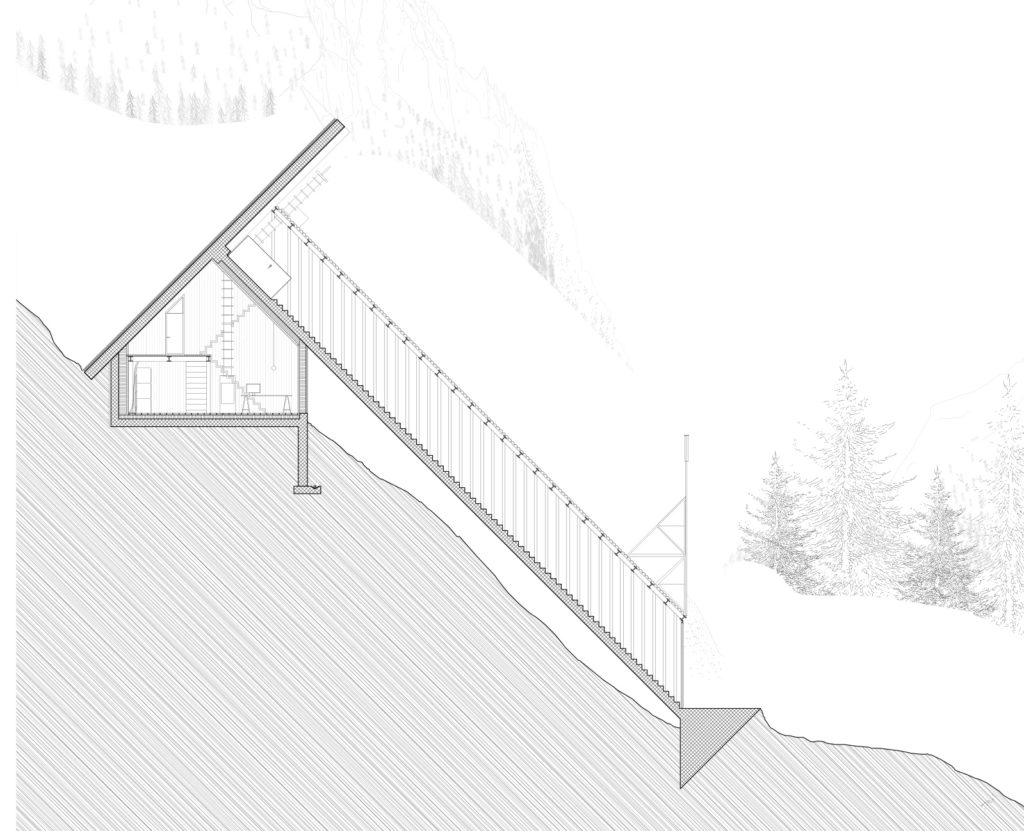

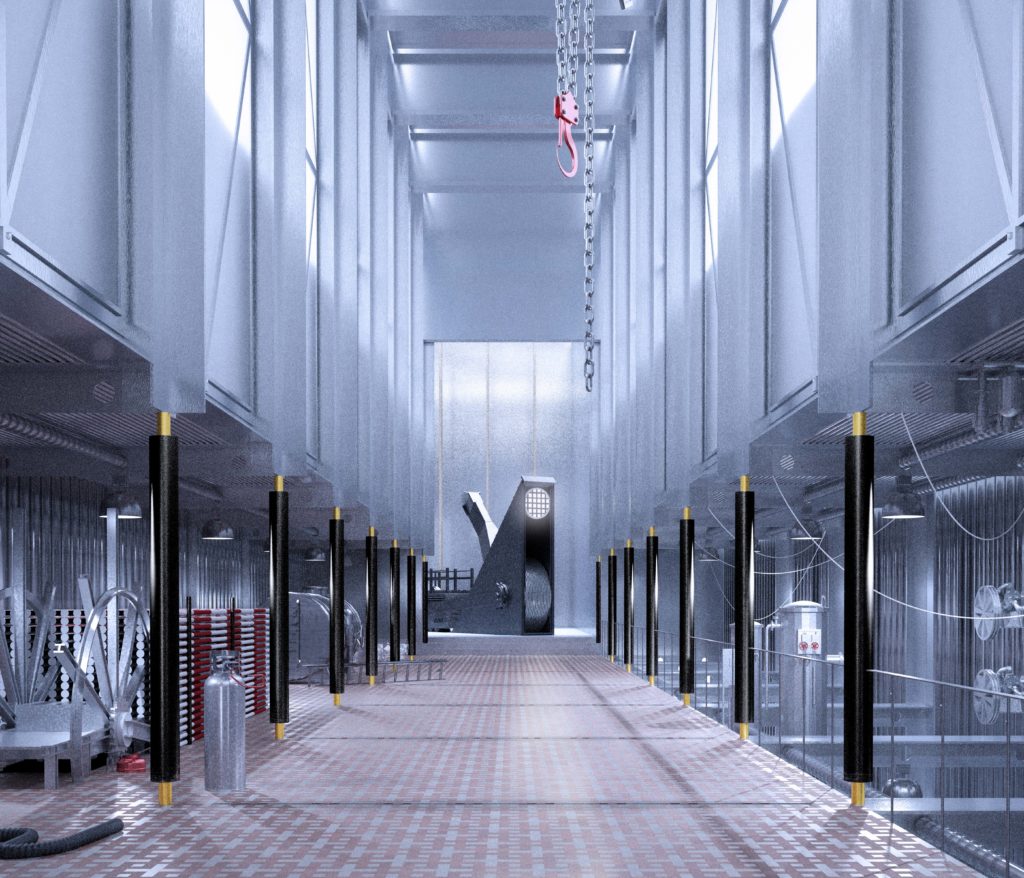

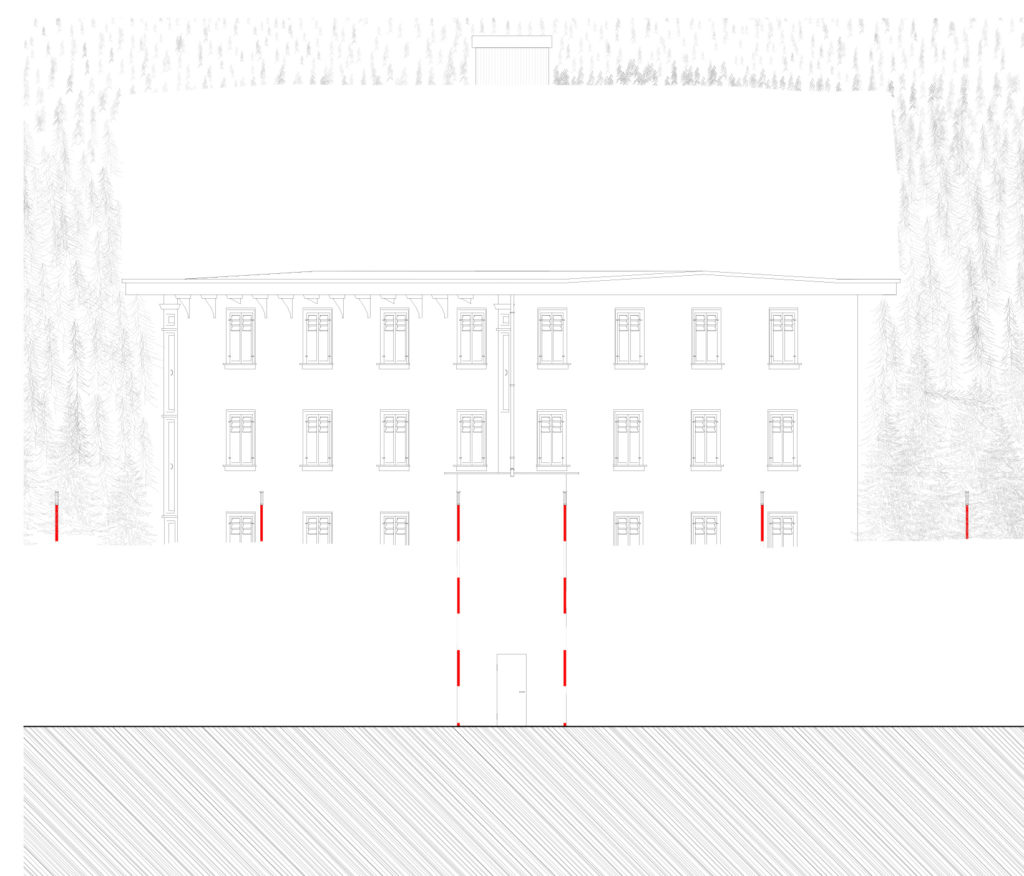

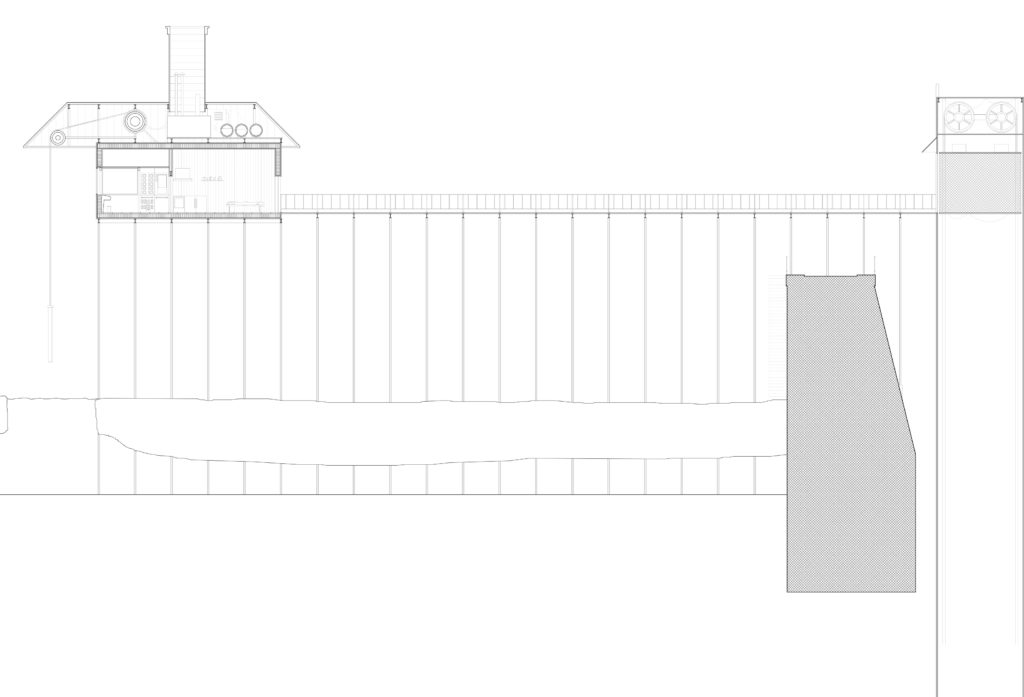

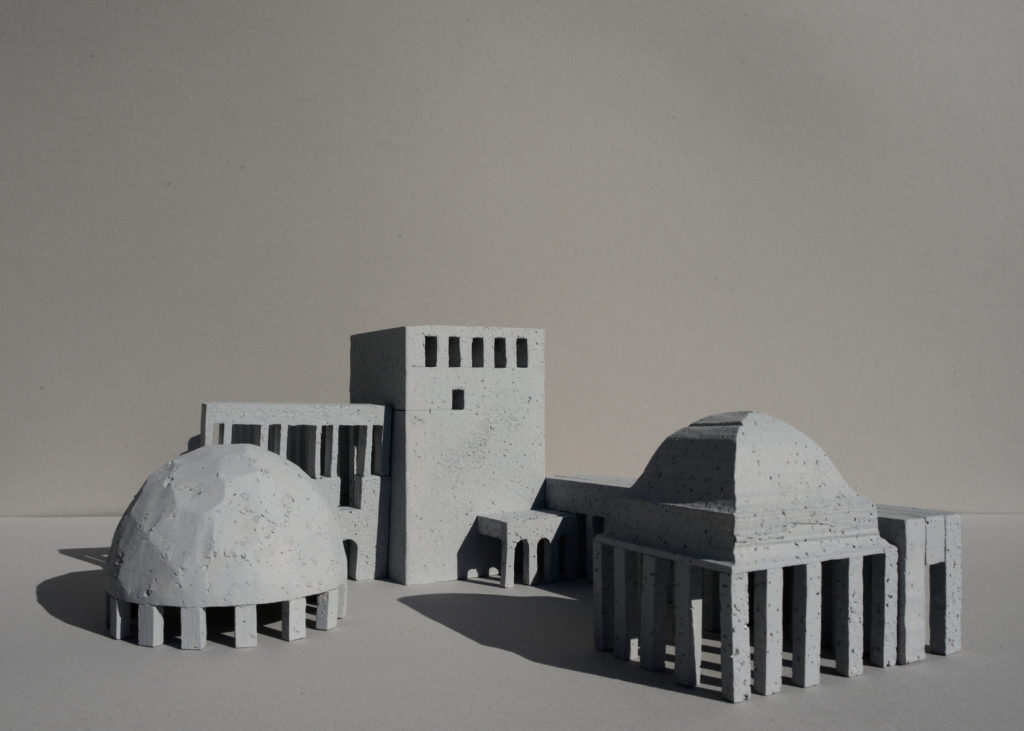

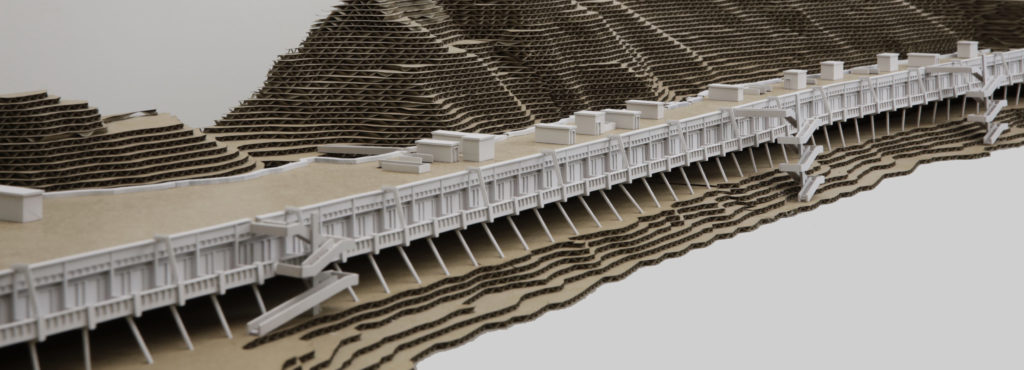

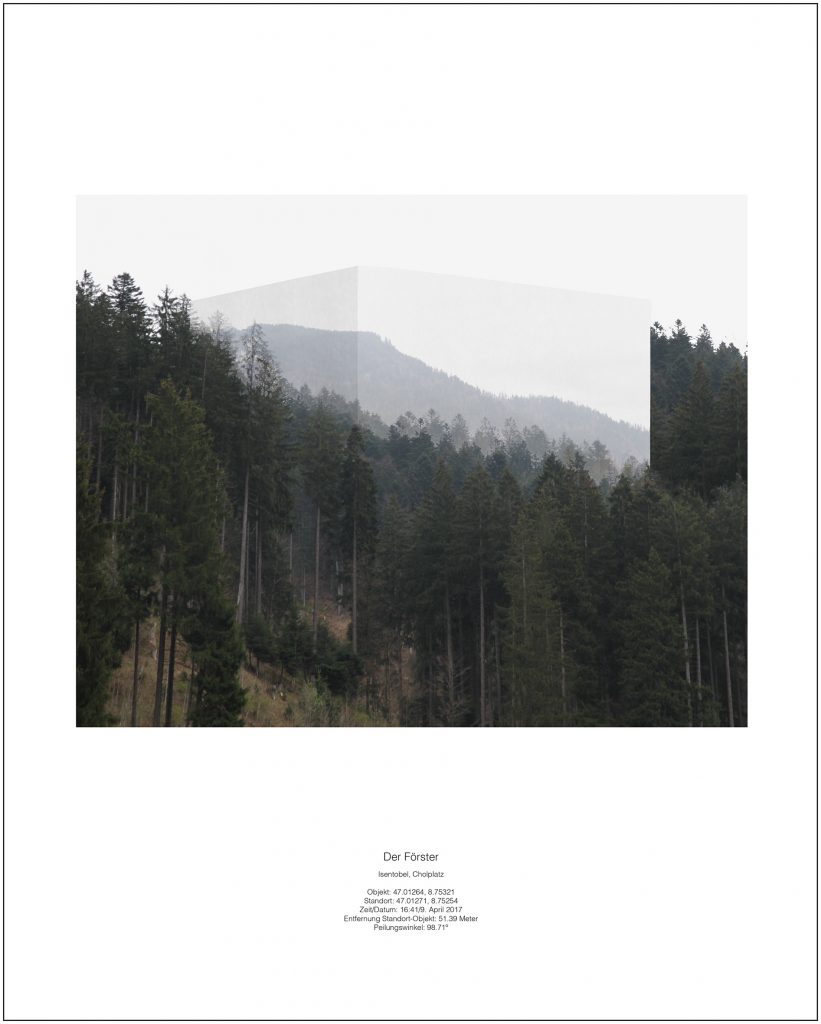

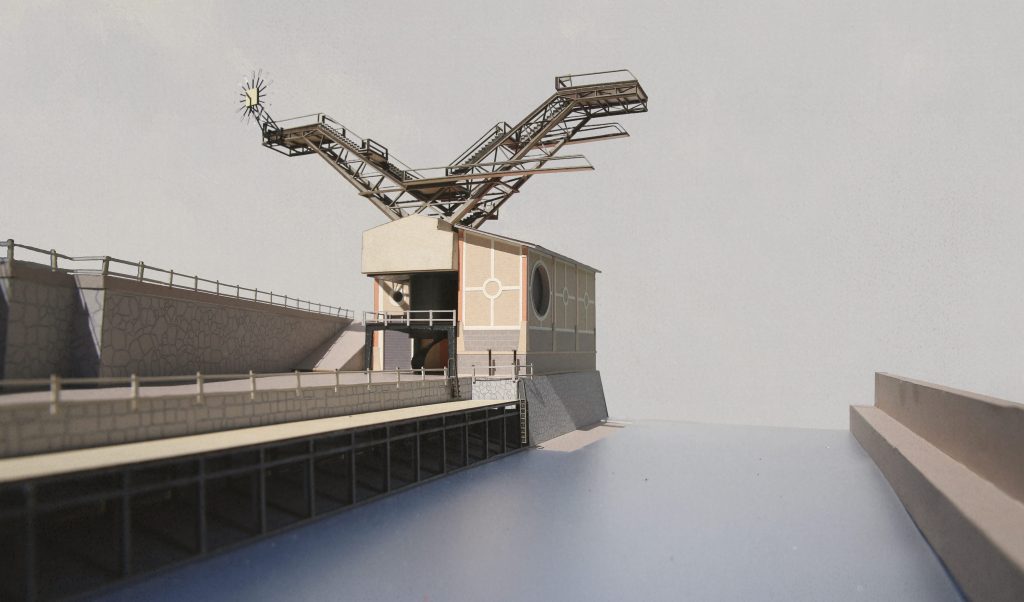

The project stages the winter of the last 27 winter inhabitants of the Urnerboden and paints a strong picture of their rejection of the place’s latent identity crisis. You avoid a summer full of temporary breakers and tourists and experience a lonely, uncompromising winter. Their chimneys are the only ones that illuminate the valley in cold winter months as symbols of social modeling. The identity of the winter inhabitants falls with the snow and is stored in a five-meter-thick layer of snow. The demarcation of society takes place via a snow wall, which, as a physical manifestation of the cantonal border, makes an administrative border visible and conveys a sense of unease to urbanity. The Glarner snowplow, the tool for regional urbanization in winter, is mobile, but it is subject to the bureaucratic order of the cantons and their snow removal obligations. The positioning of the border forces the snow plow to initiate a turning maneuver and return to Glarnerland without clearing the Urnerboden. The lack of other means of access means that the plateau is covered by snow until spring.

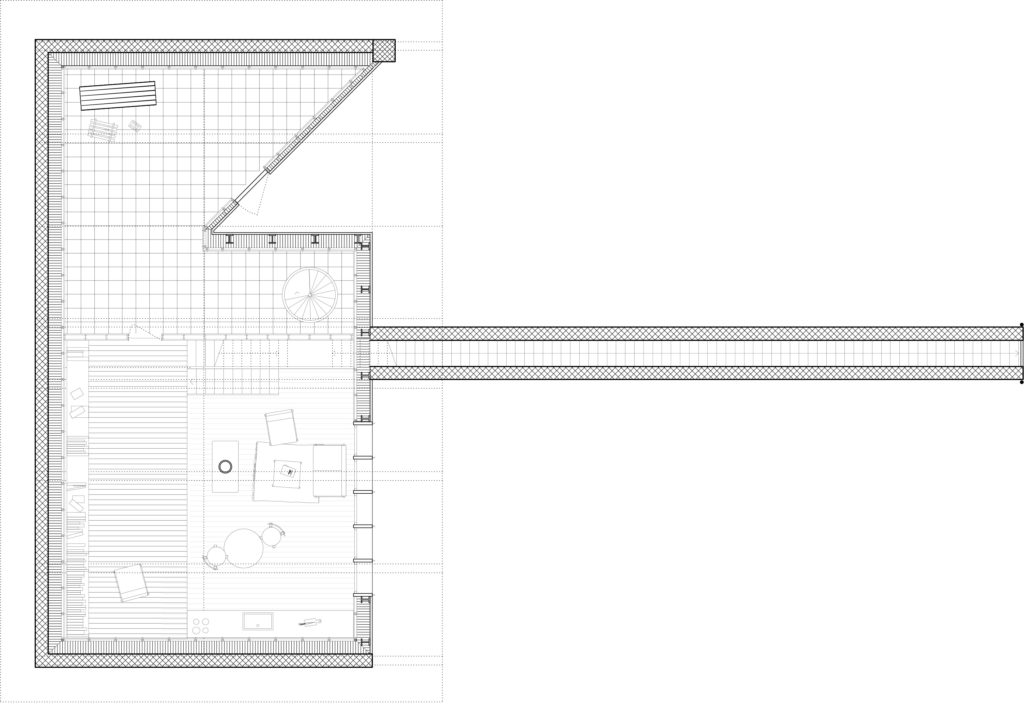

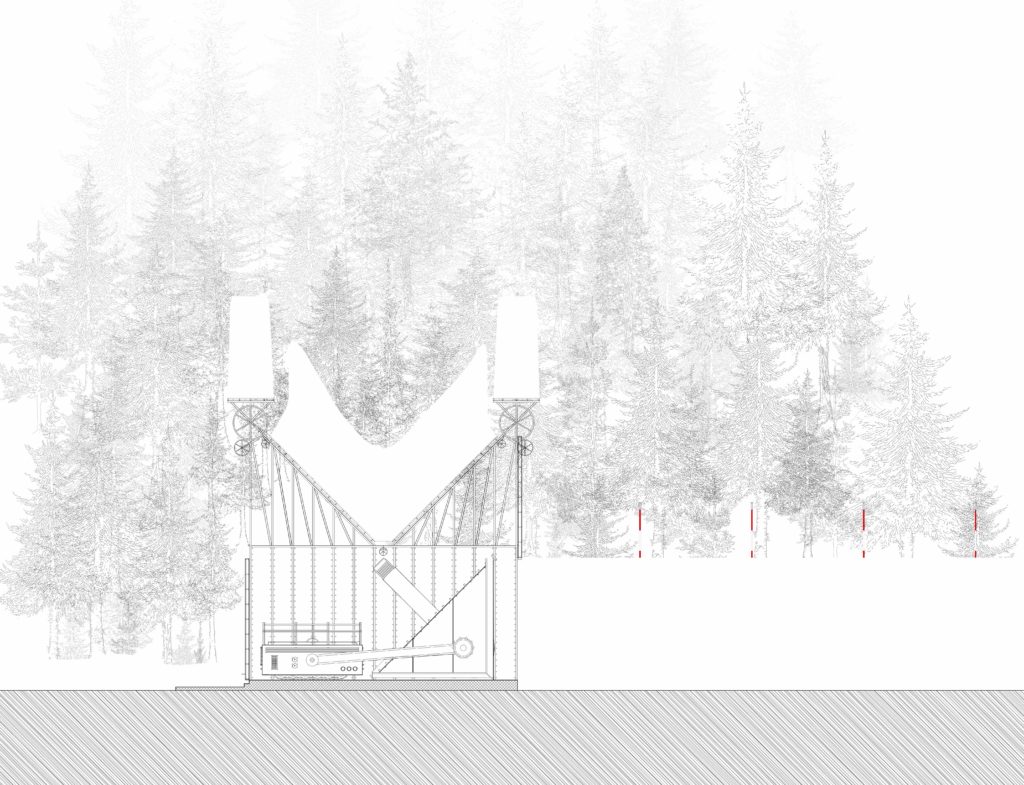

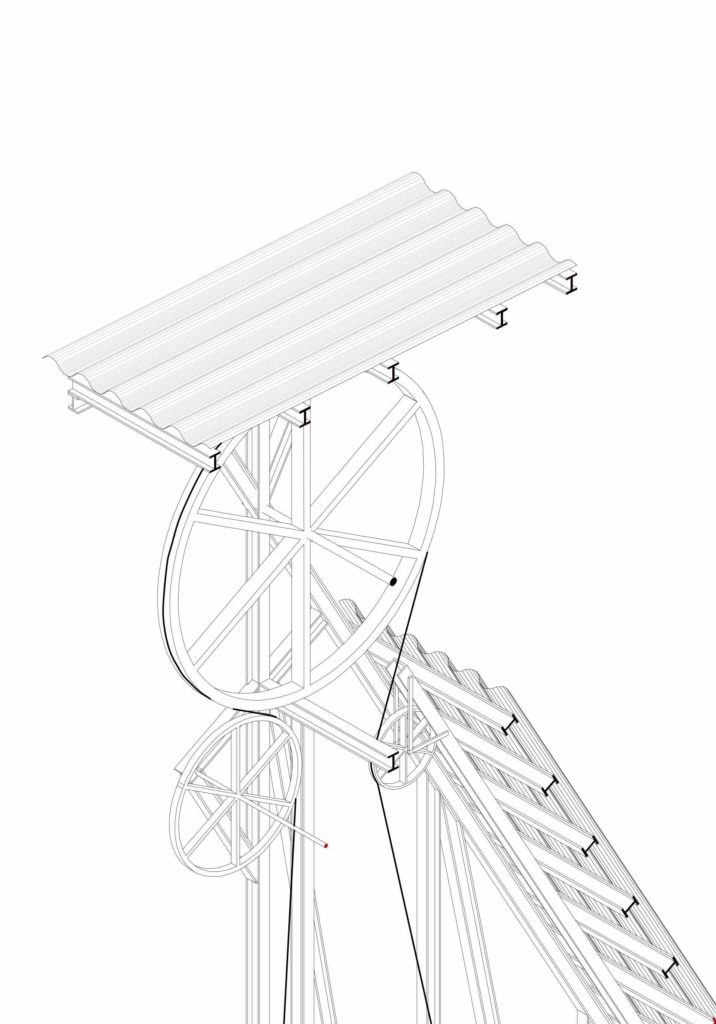

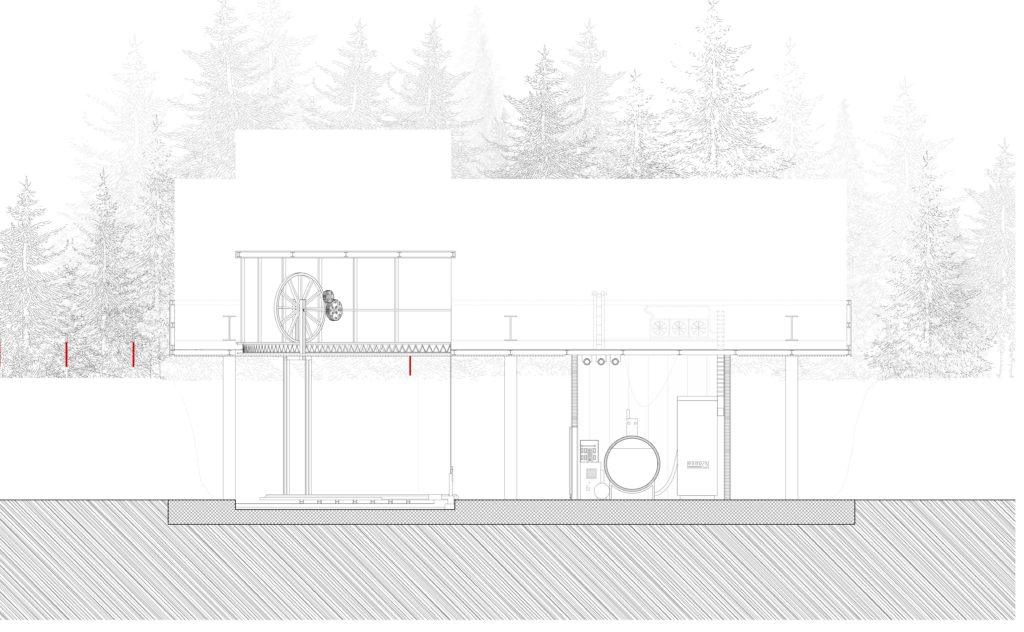

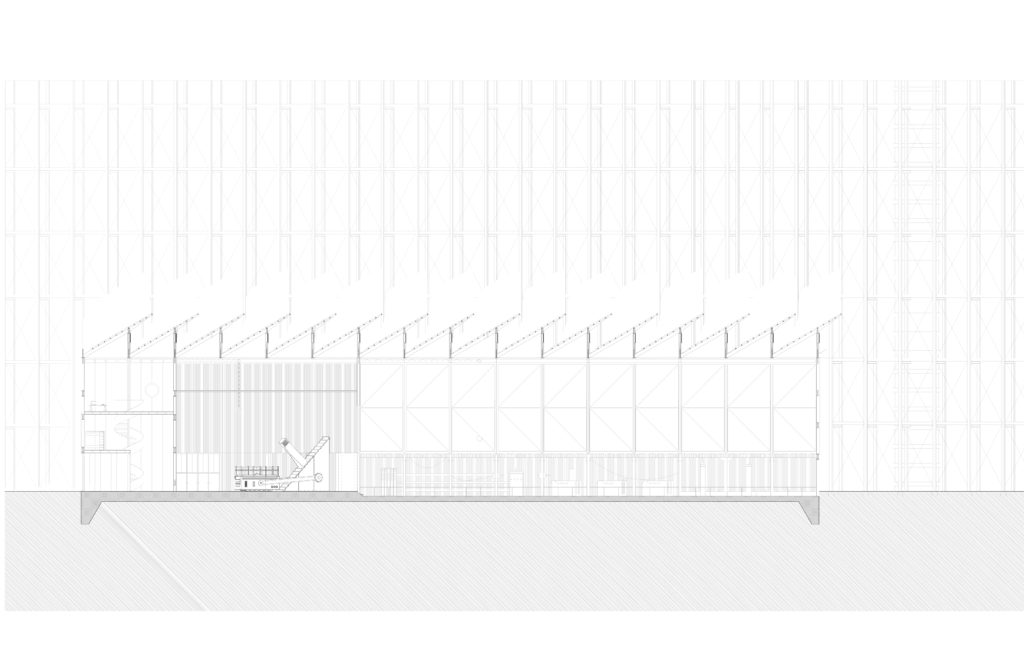

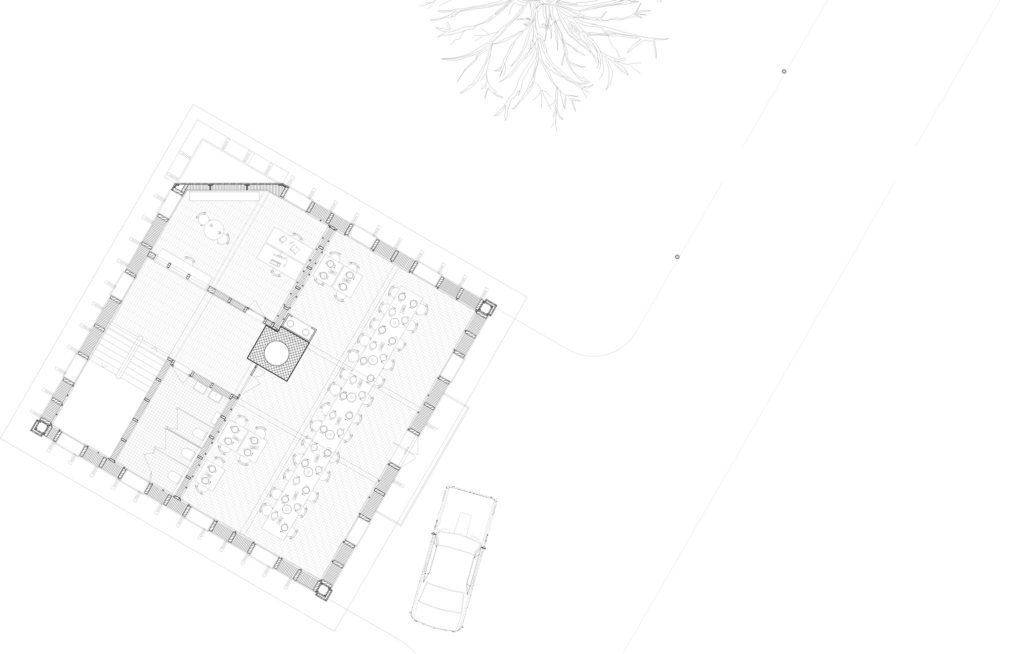

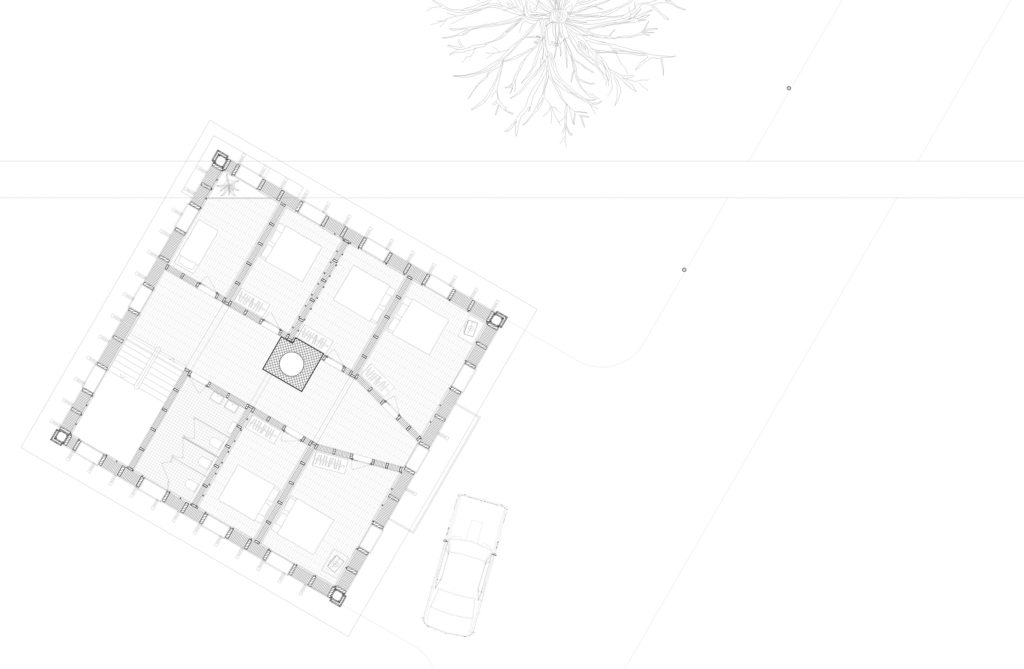

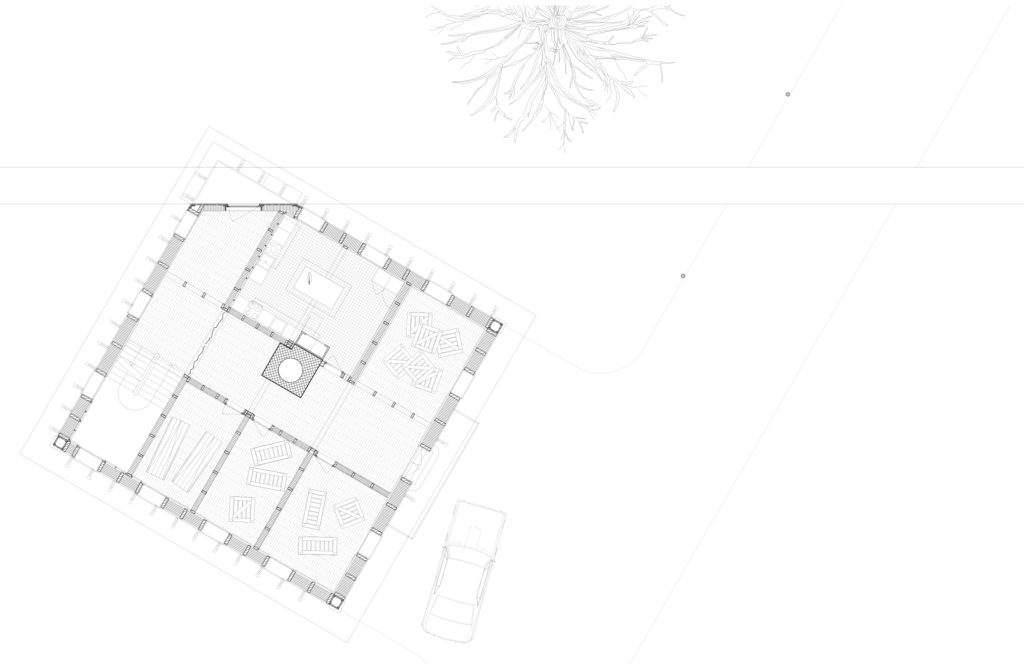

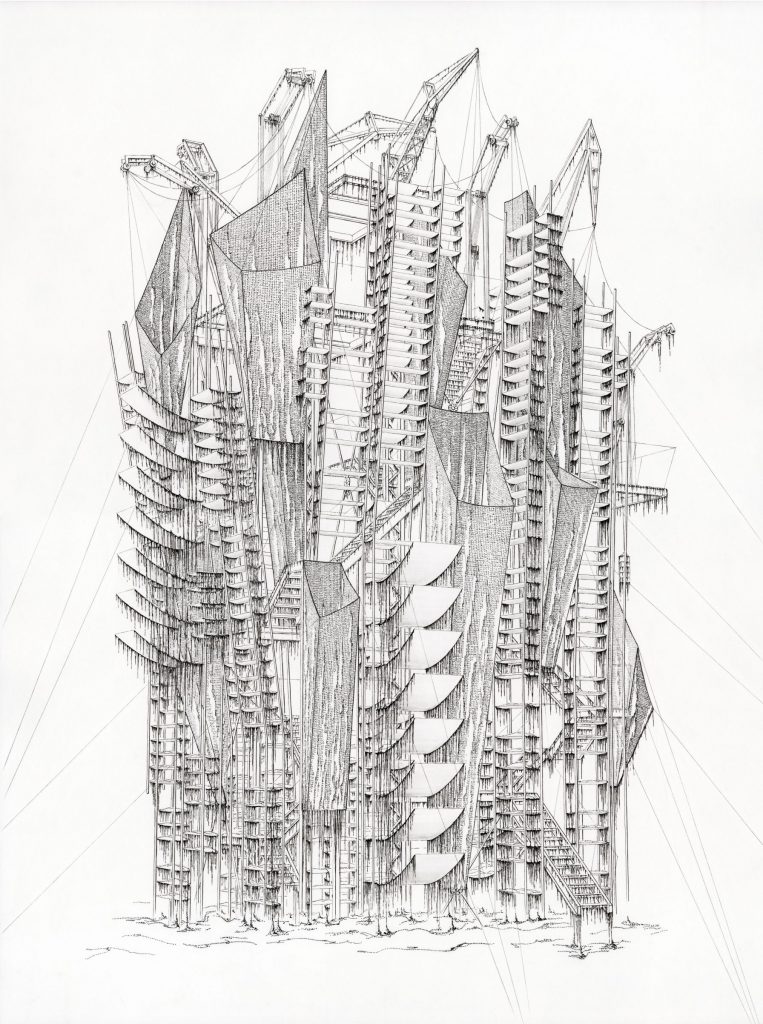

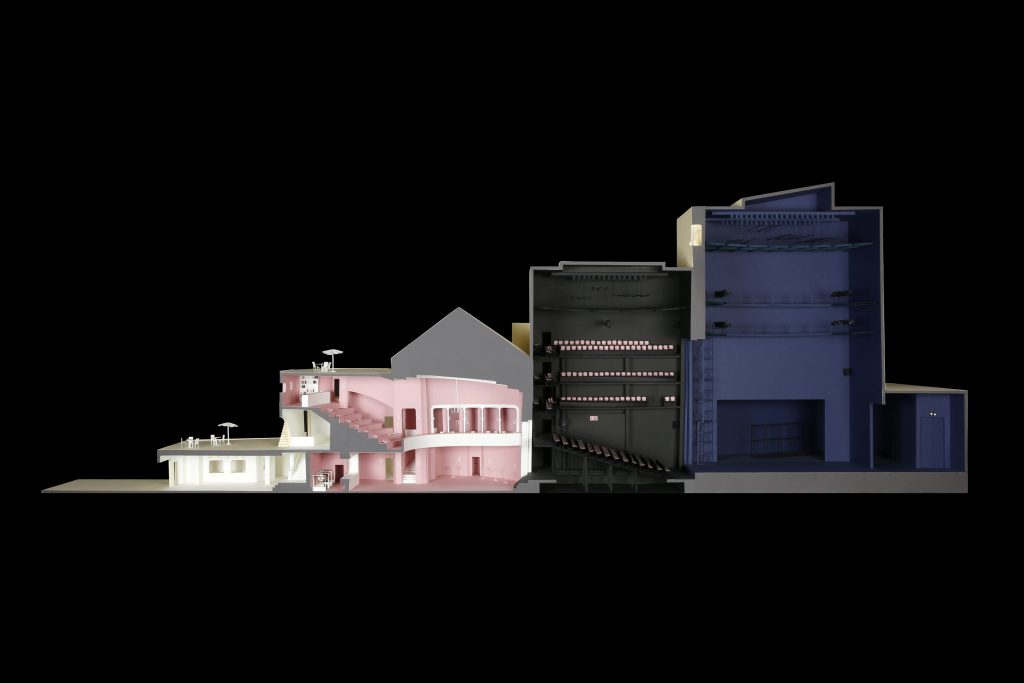

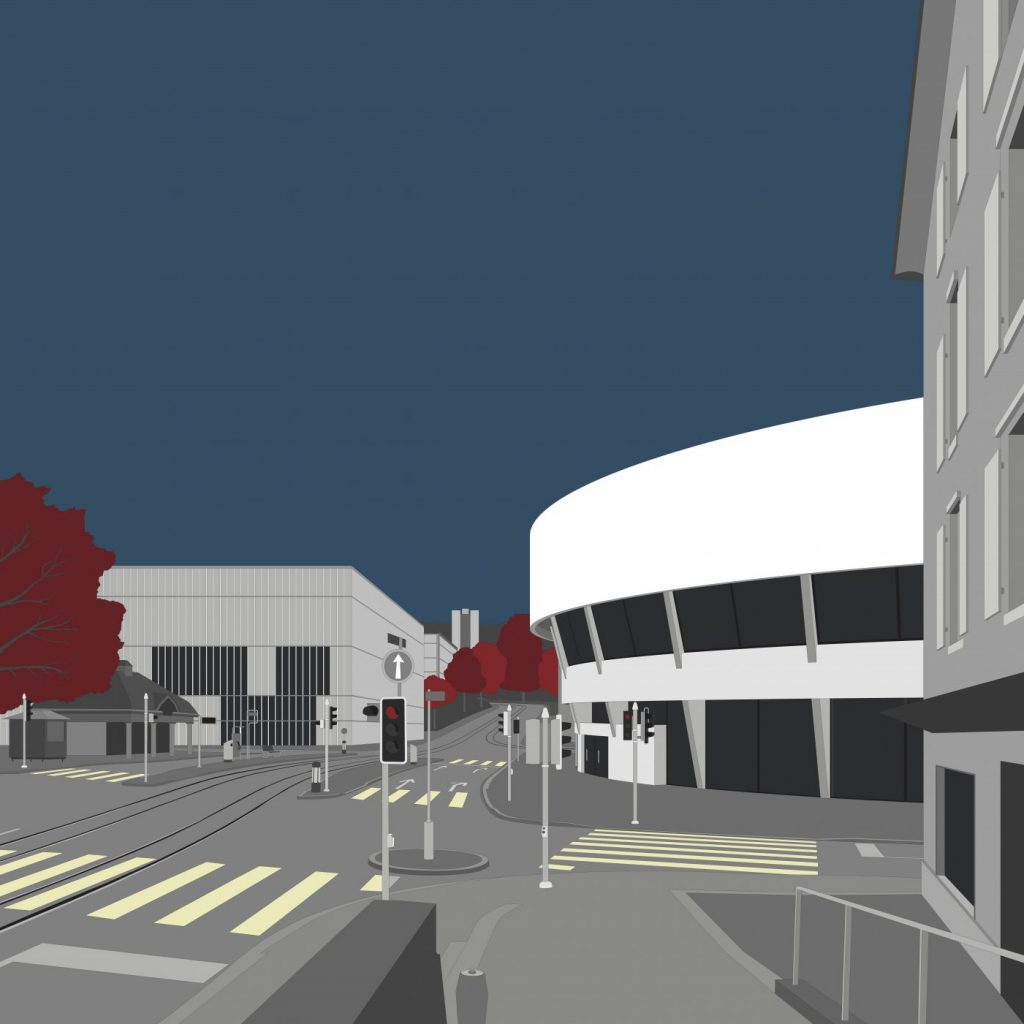

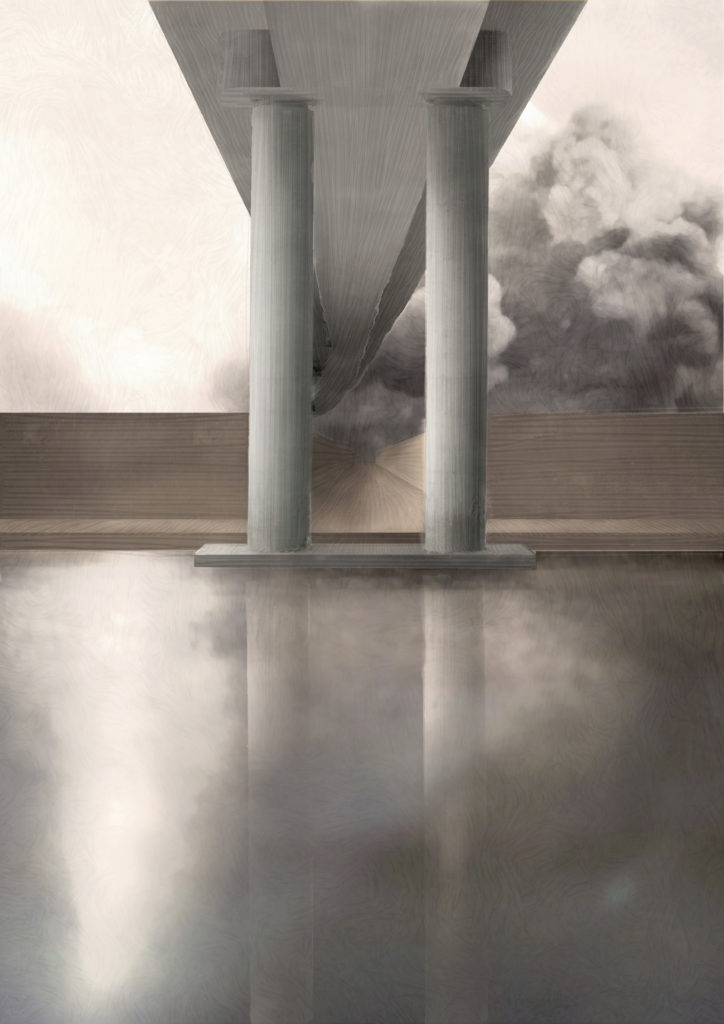

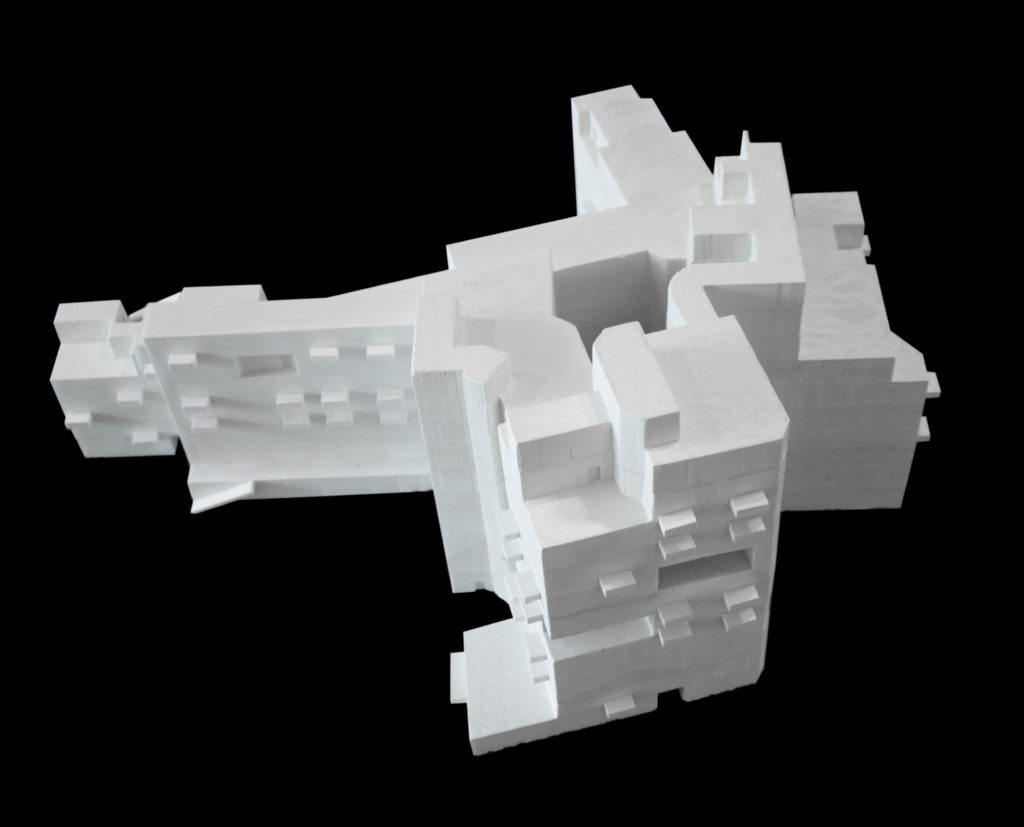

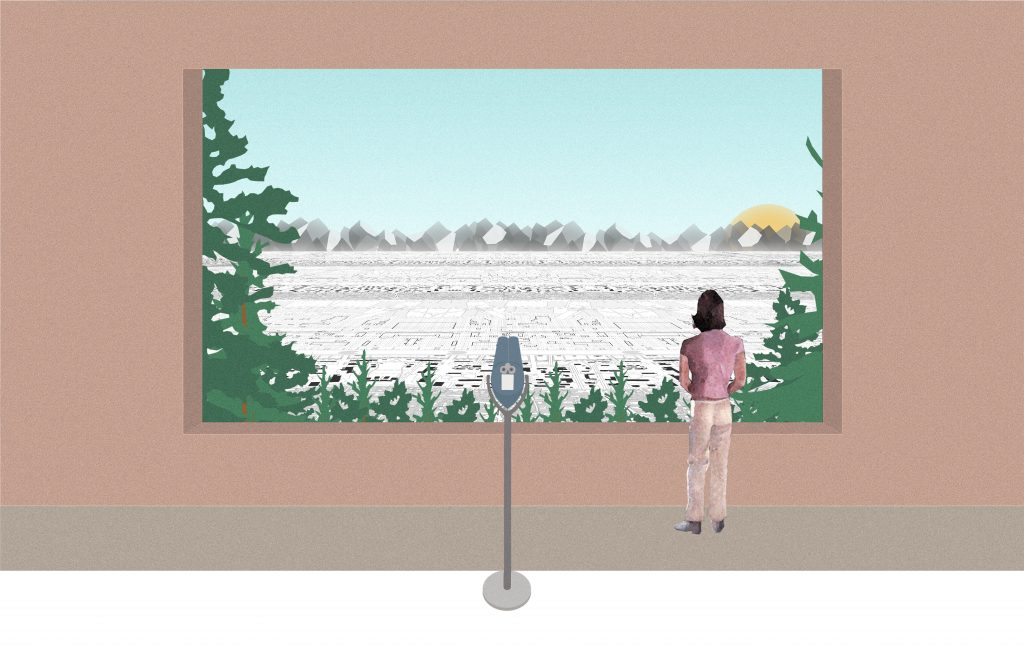

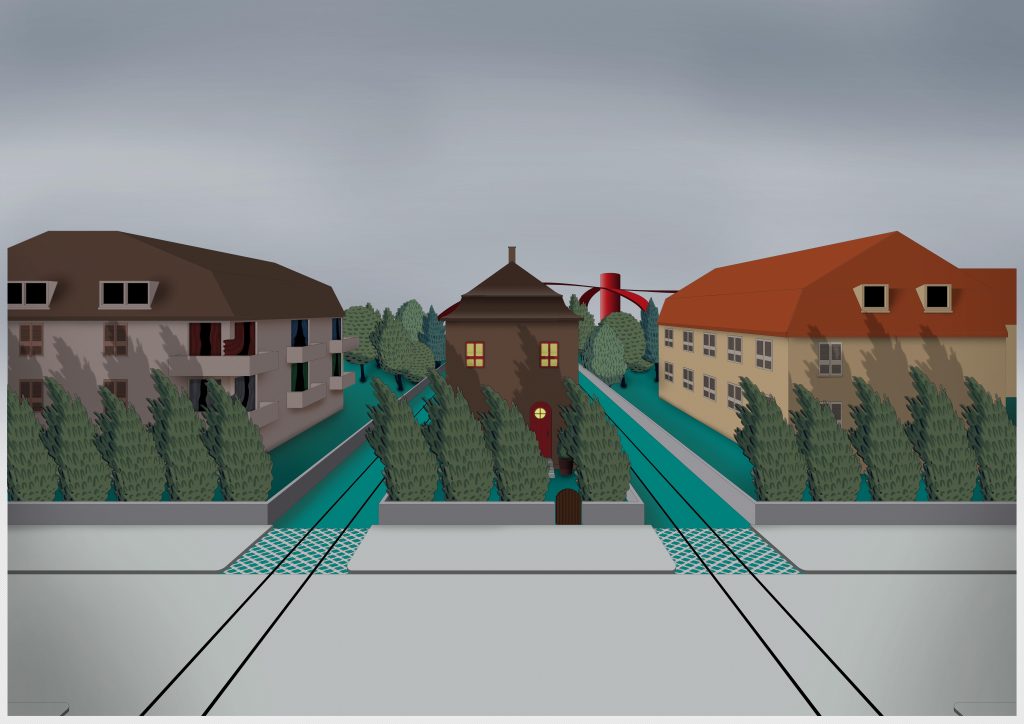

With the arrival of snow, the road disappears, the only communication artery between the Urnerboden and the outside world. The valley becomes an island, or, by embedding within a Swiss context of culturally like-minded people, a monastery. What follows is a procession that initiates the annual gathering of the project-specific society. The community enters its world through a lock and follows the symbol of its urban form, a snow blower, into the interior of the valley. The machine cuts a ditch through the white mass and halves the Urnerboden with a temporary road, which melts in the spring and unites the two halves. The ditch is the only safe way through the dazzling white landscape and the population avoids at all costs a stay on the deceptive level of the snow. In contrast to the summery road, the wintry Tabula Rasa of the valley outweighs the mathematical determination of the trench. The seemingly uncompromising trajectory is defined by a formula based on the optimization of the winter and the non-recognition of the summer. The tiller touches the houses of winter and forms an address for each house in the bottom of the ditch, five meters below the upper level of the snow desert. The urban planning form of urbanization is thus formed by an emptiness, which is depicted as a missing volume in the landscape. The construction of the snowblower allows only a linear movement. By relying on the strict hierarchies of the seasons, the machine consistently takes no account of the tree-like development structures that characterize the valley in the summer. The generally three – part sequence of Hauptstrasse – Nebenstrasse – Address is covered with snow and reduced to two levels: Graben – Address. However, the end of the valley brings with it an architecture that does not even like to pick up the snowblower; the architecture of the topography. When the slope reaches a critical value, the machine is forced to stray from its linear path and zigzag up the hill, steered by angled turnstiles. The milling machine thus takes on the role of a train, nacelle and plow in a situation that is constantly in conflict with the landscape, the architecture and its role as a means of transport. The dimensions of the trench are defined by the height and width of the snowthrower, which in turn are given by the five meter thick layer of snow. The width of 1.5 meters is generous and a challenge for the mill, since 7.5 cubic meters of snow are added per meter.