“we got it all from Lethaby, you know.”— Plastic Arts & Crafts

As many, we first engaged the modern by looking at its progeny, directing our admiration or criticism at the projects that flowed out from it. Yet, as our enthusiasm for all things modern began to fade, we turned to the advice of art critic, Dave Hickey, who once said: “Gee everything sucks, I am going to go back to the moment right before everything started sucking, and try to find a new way out of that.” So here, we turn instead to the formal output that pre-dates the modern canon, looking specifically at the houses of the Arts & Crafts Movement in the UK and the US.

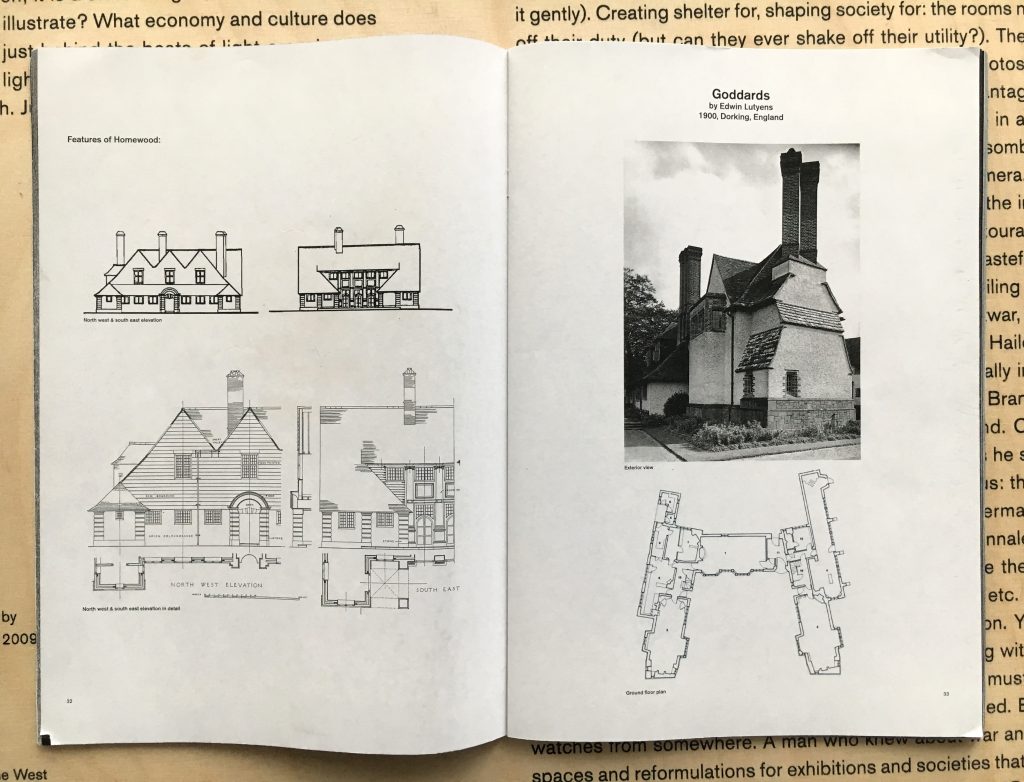

In this way, we examine some of the very same projects that were populating the pages of architectural journals in Wright and Loos’ early years. These projects by Lutyens, Mackintosh, Voysey, Shaw, Furness, Richardson and others are—perhaps surprisingly—polemical, directly challenging the dogmatic certainties of “academic architecture” in the nineteenth century. What is refreshing is that the provocative character of this work is advanced through literal spatial and architectural configurations rather than inflammatory rhetoric or the representation of externally imposed concepts. That is, expression emerges when the elements—roof, porch, drainpipe, chimney, window, dormer and door—do the talking. And this conversation is not so much with us, the audience, as it is an internal dialogue between the elements themselves.

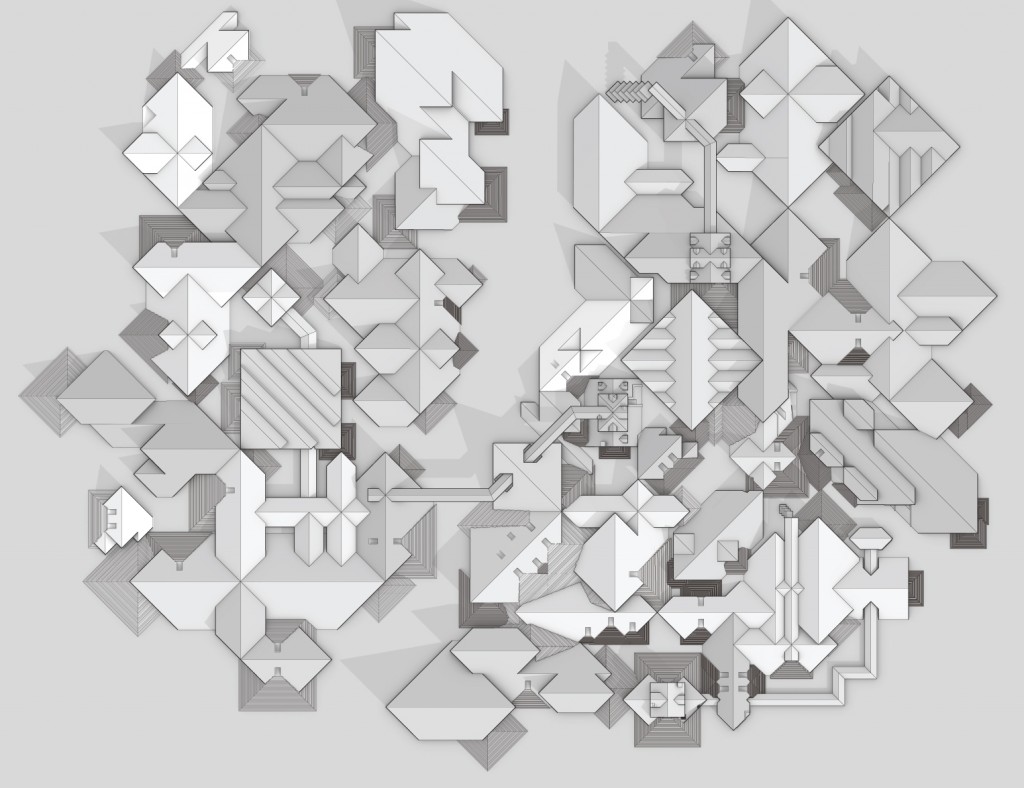

The circumstantial and combinatorial treatment of the elements in these Arts & Crafts houses work to undermine what Colin Rowe called the “architecture of ordinance,” in which design—whether in a neoclassical or early-industrial idiom—is reduced to a rule-based system of placing walls and columns on a virtual template or grid. These late-nineteenth century houses promote an element-driven architecture, where the elevational image does not derive from pre-existing rules, but rather, produces its own rules. Familiar notions of symmetry, hierarchy and order are suspended as the architectural elements conspire to put forth alternate logics of architectural organization, balance and legibility.

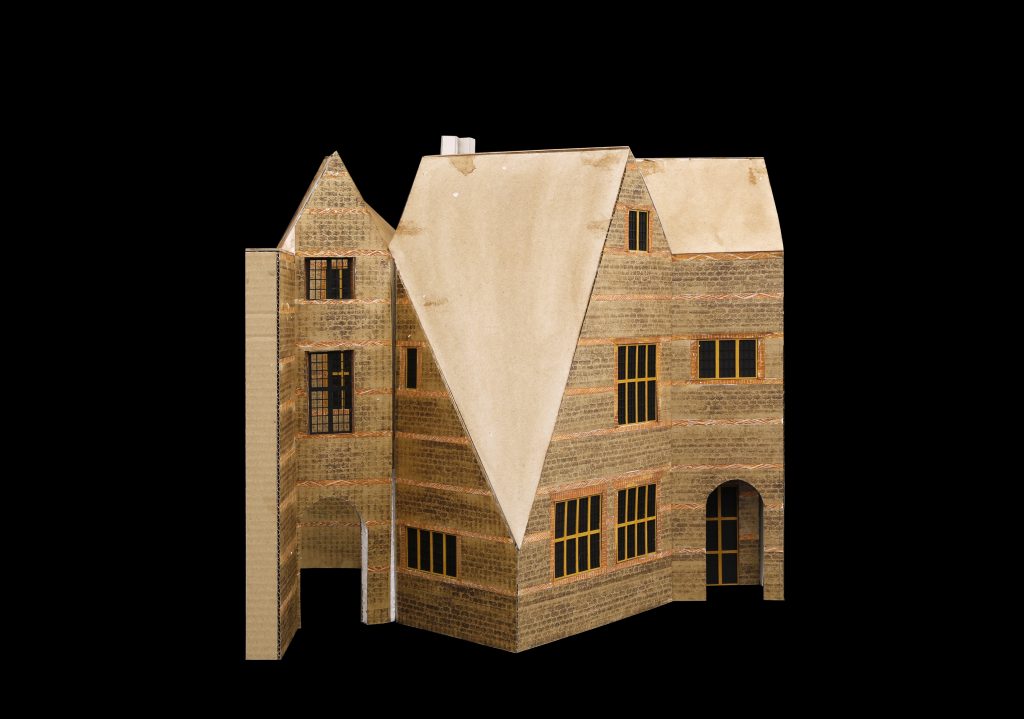

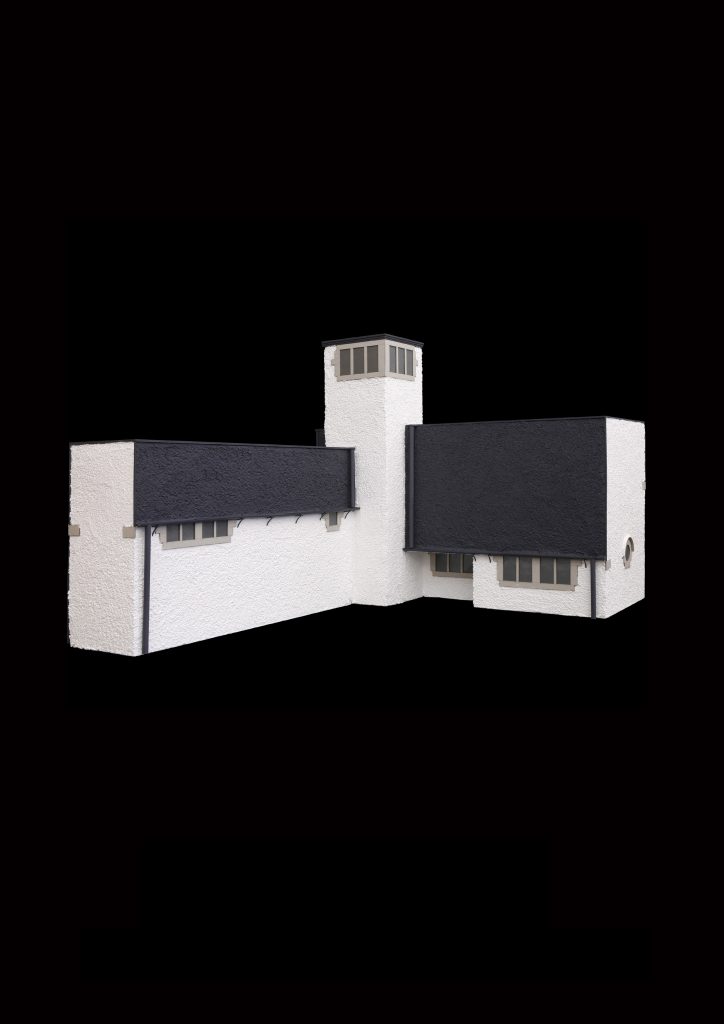

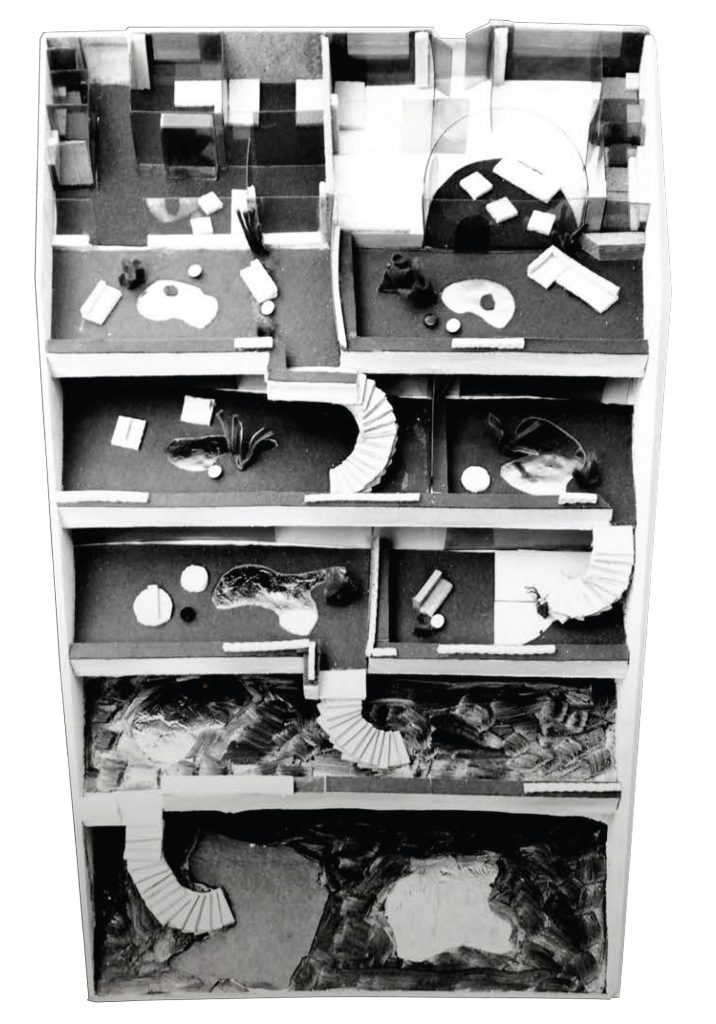

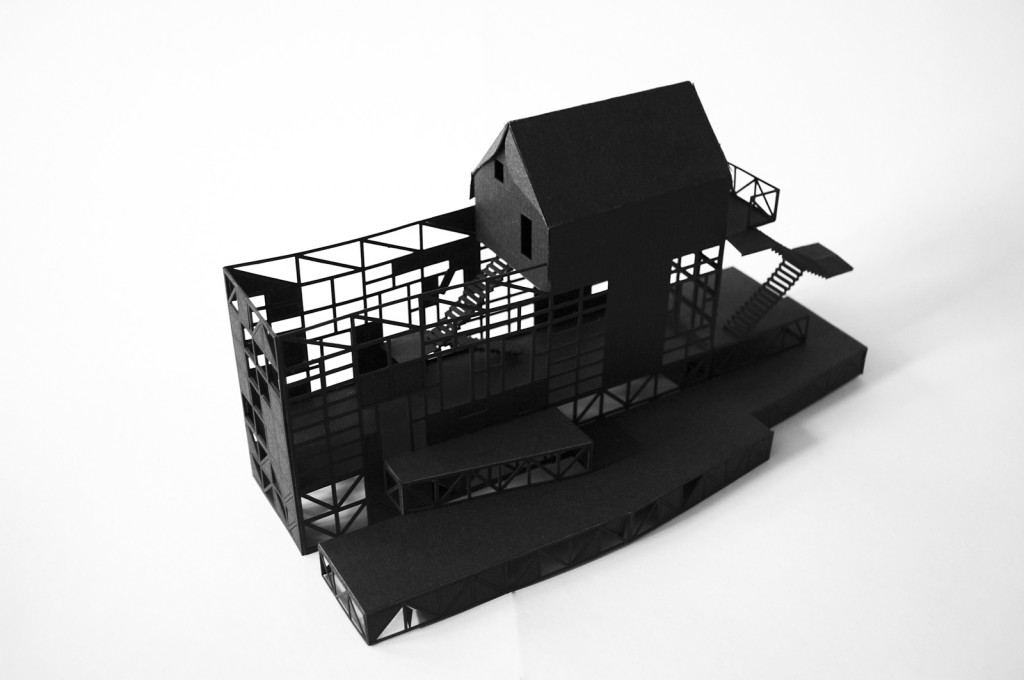

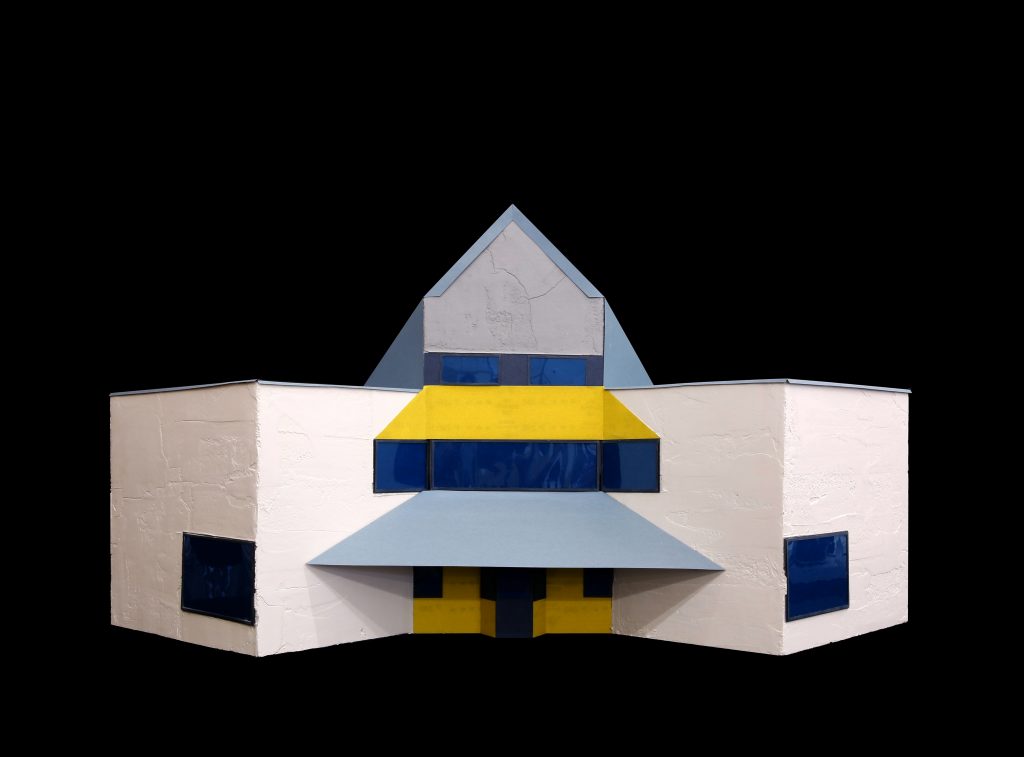

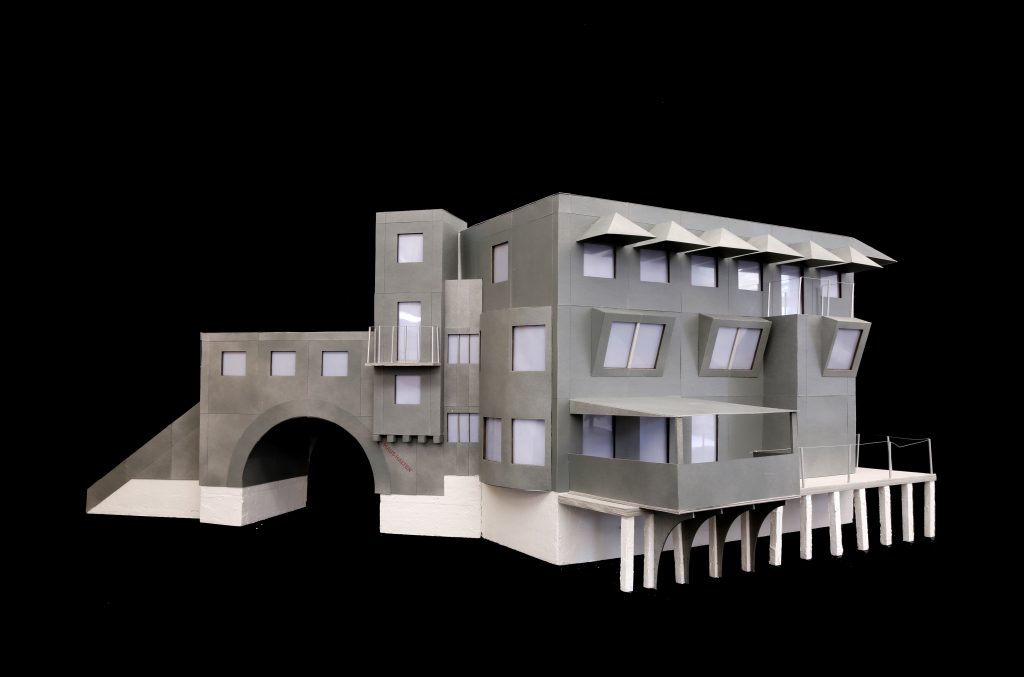

The architectural principles and inventions found in the precedents in this project—although regularly borrowed and reinterpreted by their modern successors—were never canonized or disciplined in the same way as the architecture that followed it. Thus, the projects and images remain open to new investigations and interpretations. The models featured in this pamphlet, do not simply seek to reproduce the architecture of the Arts & Crafts houses, but to distill and extract from it the unique features and principles that give these houses their “hold”. This distillation occurs not though an earnest translation, but by a collision between Arts & Crafts and its formal nightmare—a plain, white box in the dimensions of Adolf Loos’ Villa Moller at 1:20 scale.

“…we got it all from Lethaby, you know.”—Frank Lloyd Wright

Plastic interpretation:

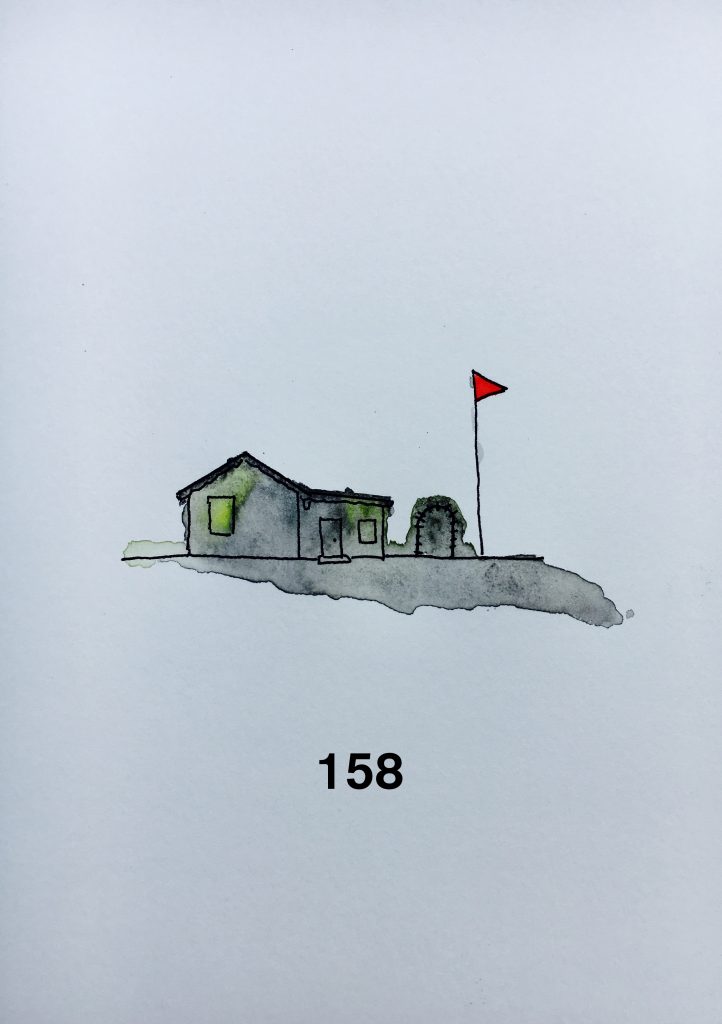

Each group of students was given (1) Arts & Crafts project and (1) 50x60x50cm styrofoam block and asked to isolate the key formal and spatial features of the reference project and project them onto the envelope of the box, allowing the precedent’s features to challenge or erode the cubic volume in favor of consolidating a new architectural whole.

Materials—

1 Arts & Crafts reference project

1 50x60x50cm styrofoam block (1:20 scale)

William R. Emerson

McKim, Mead, White